In the fifties, Cuba was a radically different place. Sporting a corrupt government with ties to both the United States and Britain, it was a pleasure ground for the very rich to vacation in an exotic locale and a terrible place for the poor to have any sort of employment at all. Many people from both the United States and Britain immigrated to Cuba and set up businesses that catered to the high-end (read: white) clientele. Our Man in Havana concerns a British man who is in the vacuum cleaner business. The high political tension and the covert espionage of this period was enough to sweep even this innocent man into the entire mess.

James Wormold is just an ordinary vacuum cleaner salesman with a daughter. He is having money troubles because he wants to provide a good life for her daughter but she has expensive tastes (mainly horses). One day a mysterious cloaked British man enters the shop and gives Wormold a proposal. He wants to recruit him into the spy business, but neglects to give him any training or advice. Just a deadline and money. But by accepting that money, he must deliver some information. So he produces a sketch he had made of a vacuum cleaner and claims it to be bomb testing site. Meanwhile, Wormold’s daughter, Milly, makes friends with a Cuban general at the stables and he does nothing but hit on her constantly and make Wormold paranoid. Once the British get a hold of the documents, they consider it the most valuable evidence they have ever gotten and take it at face value. They send a witty young woman, Beatrice, to act as his secretary and to make sure everything he is getting is right. Meanwhile the Cuban government gets wind of Wormold’s activities and goes on a hunt for him that includes getting his friend, Dr. Hasselbacher, into trouble. Wormold must now get out of a severe pickle while also maintaining a level of calm for Milly.

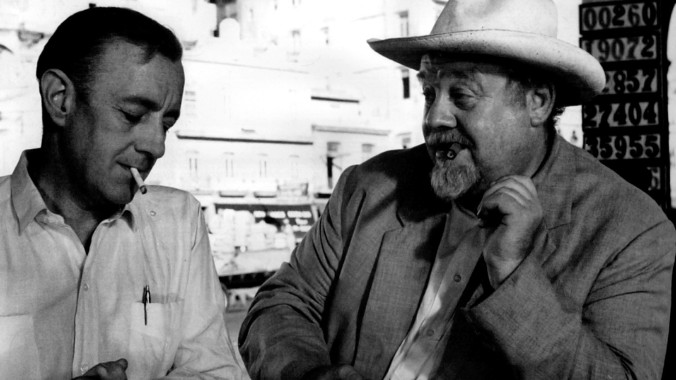

So far I have neglected to tell you the people behind the picture. This is important because of who these people are. Carol Reed and Graham Greene reunite with this movie and serve as director and writer respectively. Their most famous collaboration was the Third Man, considered to be a noir masterpiece. Playing Wormold was Alec Guinness, who has the best stone face since Keaton. Dr. Hasselbacher is Burl Ives, Beatrice is Maureen O’Hara, and Noel Coward (the director) is the recruiter at the beginning. Without any of these people, this movie would have been terrible. But Guinness, O’Hara, Greene, Reed, Ives, and Coward are all able to bring a sardonic wit to this movie that is refreshing and unique. They elevate the material and give it an absurd bent. But most of all they are able to shed light on the problem of the spying game and how terrible misinformation can be to the fate of one person (although maybe not the whole country).

While the movie hints at rising political tensions, the movie was made overtly during them. The Cuban was happening as the film was being shot on location in Havana. Castro allowed this movie to be filmed there for reasons that are unknown, given his followup to the movie wrapping up that there will no longer be a safe way to get in and out. Castro also made overt threats to the United States thus ensuring Hollywood would never venture that world again (at least not on location.)